I just finished the time-manipulation puzzle game Braid and I absolutely loved it. I highly recommend playing it on XBLA, so you can contemplate the game on a comfortable couch, with an ergonomic controller in your hands. Normally, I dislike platform games; they require too much in the way of twitch skills and are too punitive (for failing a tweaky jump, for instance). Braid is the best game I’ve played on XBLA and one of my favorite games in a while.

The game’s level progression is satisfyingly consistent and cohesively domestic: A number of worlds, accessible from within a house. (Why won’t someone please turn House of Leaves into a game, btw?) Each world has levels with the same global mechanics. But each world also has one amazing new mechanic. The player is shown the rules—both the consistent, global rules and the new world-specific mechanics—in a gentle fashion. Each world’s completion is tracked with a painting, broken up into puzzle pieces.

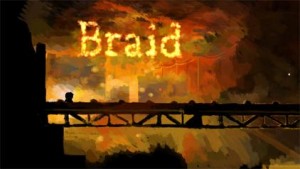

The music and art for Braid are such a huge, integrated part of the experience that all the elements seem to elevate one another. “Unity of Effect” as Poe (or my friend and fellow game designer Ricardo Bare) might say. Partially, this might be aided by the fact that altering time during gameplay also alters the music. Further, a critical pragmatic point is the way the music changes from level to level and during rewind; since you spend a lot of time considering a given puzzle, repetitive music in Braid would likely kill your mind. Instead, the music is almost a companion and feels organically different and appropriate from moment to moment. In terms of visuals, I love the somber, painterly art style. It’s great to see something simultaneously atypical and really well executed. The game is just beautiful and the art style evokes the same feelings and concepts supported holistically by the other elements in the game, including the gameplay dynamics.

The rich, interesting background fiction for Braid is refreshing in a world of game content based on soldiers, aliens, knights, demons and spies. (Okay, admittedly, I still love that stuff, but it’s nice to have alternatives.) I love the time mechanics and the *generally* forgiving arcade play, but the cohesion of the elements and the atypical fiction were equally important to my experience. I also loved the feeling of constant allusions and metaphor. I had a teary-eyed fifth grade moment at one point and realized that I felt some sadness related to subjective memories of the Lord of the Rings books.

Most of the time, I loved figuring out the puzzles as much as I loved the cohesive vibe. To complete the game, I had to look up the solutions to three puzzle pieces, which I didn’t mind doing at all. For a guy with zero patience, only needing 3 hints to complete a mind-bender like this is hugely cool and a sign of the game’s polish.

An intermittent frustration involved places in the game where I figured out the puzzle but (felt like I) lacked the arcade skills to complete them without trying dozens of times, even with rewind. It’s hard to criticize a platformer for tricky jumps or a puzzle game for hard puzzles; especially if that game allows you to rewind mistakes and generally continue play without solving all of the puzzles. (Being able to leave a puzzle behind, returning to it later, is one of the best decisions related to the game’s level flow.) But once in a while the game nearly drove me mad. The larger issue, really, is knowing whether your planned approach to a puzzle is right or wrong. You might have an idea about how to solve the puzzle, but fail a jump several times and thus doubt your plan. So you move on and try another (flawed) approach. After a while, this doubt screws with you in other ways too. For the Fickle Companion puzzle, I first spent a lot of time working on a suboptimal semi-solution that *seemed* right; I tried one jump dozens of times, assuming it would eventually work.

That leads me to another critique. I believe that one of Braid’s strengths also points to a weakness: It feels like a heavily-authored experience, with little room for self-expression. Since that’s key to most of the games I love, I missed it here. (Oddly, Portal didn’t feel this way for me; perhaps the visceral movement through 3d FPS space gives Portal a sense of expressive movement, even though the puzzles generally have, I believe, a single solution.)

But the game is really about discovery. It plays to this strength and early on I had this feeling that the game was encouraging me to re-think the punitive designer/player compact. (And that’s a great achievement in game design.) I’m allowed to simply walk along almost to the end of the game? I can back up and correct any mistake? In general, softening failure is such a great direction to expand games. Randy Smith alluded to it in a GDC talk a while back, games like Prey tackled the concept in FPS form a year or so back, and recently Rock Band in tour mode has my favorite soft death/failure ever. (Not only are you given multiple chances to avoid dipping too low, but when you do omg it feels good to be saved or to save someone.) Braid really nails this concept. After a while, I felt oddly *comfortable* in the rules space of the game.

Whereas in many cases, platformers make it easy to figure out what you need to do, then vex you with overly-hard execution tasks, Braid makes execution fairly easy (in most cases), but requires devilish thought to figure out how a given puzzle can be solved. Braid reminds me of Portal (another favorite) in the way it allowed me to engage my mind at my own pace. By the time I finished the game, I was ready for it to end. I’ve heard that there are additional hidden elements that one can go back and pursue, but—having resolved the story—I don’t feel any desire to explore that aspect of the game.

Forbidden words…is Braid better than Mario 64? The latter game, when it came out, seemed like a revolution. It was so amazingly well done that it taught us all something about game design. Mario 64 is the work of one of the best game designers in the world and playing the game felt like attending his class as a very fortunate pupil.

But in Braid I have a sense of the little jumping avatar…who he is and how he might feel. The dimensions of his being are lightly but powerfully defined through snippets of fiction and through the metaphors involved in gameplay…undoing fundamentally life-altering mistakes, remorse. That’s meaningful to me. Mario 64 features some really clever timed jumping puzzles and generally (aside from the wall jump and the camera moving into bad spots) great controls. But Braid’s puzzles are nothing short of mind-altering…after finishing some of them I felt like my brain had been made more flexible, like I’d learned a new concept in some intimate new language. This is an order of magnitude in difference. Braid takes a simple concept—rescue the princess—and turns it into something deeply moving, something I’ll be thinking about for years. Braid is full of touching allusions of other games, works of fiction, and universal life experiences. Every inch of Braid is a painting; the core game dynamics make music. Unlike most platformers, Braid is forgiving; when you miss a jump, you simply back up time, and the visuals and audio cues associated with this mechanic are pleasing of themselves, aesthetically, while also supporting the underlying fiction.

Braid is amazing.